Recent Studies

How do risk and time preferences develop across cultures?

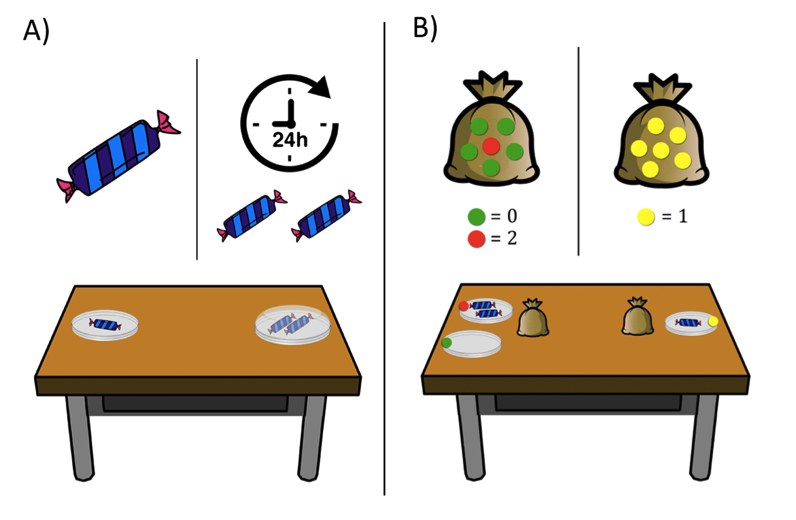

Dating back to the Marshmallow Task of the 1970s, psychologists have long been interested in the development of patience and impulsivity among children. However, the vast majority of work on this topic has been conducted entirely among Western children, who live in very different environments than most other children in the world. In this study, we wanted to investigate how time preferences — how much you value the present over the future — and risk preferences — how much you value guaranteed rewards over riskier ones — develop across different environments. To explore this question, we created two novel games for children to play. In the time task, children are offered choices between candy they can eat today versus candy they have to wait for tomorrow to eat. In the risk task, children are offered the choice between a guaranteed reward and one that is less likely but generally greater in value.

In order to understand how different environments may lead to different preferences, we conducted this study among American children in New Haven, Toba children in Argentina, Indian schoolchildren in Gujarat, and indigenous Shuar children in Amazonian Ecuador.

We find that across all four countries, children are sensitive to reward outcome, generally preferring the tomorrow reward or risky reward as the reward amount increases. However, we also find interesting cross-cultural differences.

When it comes to risk preferences, children in India, the US, and Argentina tend to prefer the risky options, while Shuar children overwhelmingly prefer the safe options. Risk preferences also show an interesting developmental pattern, with India, American, and Argentinian children starting out risk-seeking and eventually becoming more risk-averse, while Shuar children start out risk-averse and generally become more risk-seeking.

We see an interesting pattern in time preferences as well. We find that all children become more patient with age. However, we again see a pattern such that children from India, the US, and Argentina group together, generally preferring tomorrow rewards, while Shuar children consolidate candy so that they have it either all today or all tomorrow.

These findings are the first to highlight that cross-cultural differences in risk preferences and time preferences exist, and that they can be traced into childhood. Deploying a cross-cultural perspective can help us better understand the diversity of cognitive development in the world and begin to assess which environmental cues may be important in promoting this variability.

Children’s Evaluations of Free Riders

We often engage in group activities in life (e.g., a potluck dinner), which can only be successful if everyone contributes to it. But individuals might be tempted to free ride--to benefit without contributing (e.g., bringing no food to the potluck). We are interested in how children evaluate free riders--is it OK to free ride, since other members may share the responsibility and contributing to the group should be a voluntary choice?

We presented 4-10-year-olds stories about group activities, in which the group will get a bigger reward (e.g., a bigger cake) if more members donate their belongings (e.g., chocolate). Three of the members contribute but one free ride. We found that even the youngest children viewed the free rider as bad and disliked him compared to contributors.

In two different stories, we also changed the outcome (i.e., the group got the biggest reward despite the presence of the free rider) or the number of free riders (i.e., half of the group free ride), but young children still negatively evaluated the free riders, suggesting it is the intentional act of free riding that children dislike.

These results provide strong evidence that we negatively evaluate free riders from early in life. The robust aversion to free riding may deter the occurrence of these behaviors and thus could be an important mechanism to support group-level cooperation.

Why do we like members of our groups?

Our society is organized in many different groups, such as classroom groups, sports teams or circles of friends. We have a very strong tendency to form groups with others and take these groups very seriously. Even when we have never met our group members before, we tend to like them more than members of other groups. For example, already at the beginning of a new school year, children often prefer their classmates to the children who go to other classrooms or schools.

In this study, we investigate the origins of this phenomenon. One possibility is that this tendency helps us to get ready to work together with our group members. To test this hypothesis, children are allocated into one of two color groups and are told that they will now play with their group members. In the experimental condition, due to "technical problems", the child cannot play with the in-group members, but has to collaborate with children from the other group instead. We then measure whether children's preference for their own group persists, or whether their preference shifted to their outgroup members to prepare them for the upcoming collaboration.

Do children expect a gender gap in wages?

While a great deal of work is focused on understanding the gender gap in wages in adults, we know virtually nothing about whether children also expect males and females to be compensated differently for performing the same work.

In our society, men are frequently paid more than women for doing the same job, a phenomenon known as the gender gap in wages. This phenomenon is striking for two reasons. First, both men and women show strong preferences for equality in laboratory experiments so it is surprising that such a strong pattern of inequality is allowed to persist. Second, when people are asked which gender they prefer, both men and women show preferences for women. While a great deal of work is focused on understanding the gender gap in wages in adults, we know virtually nothing about whether children also expect males and females to be compensated differently for performing the same work.

An example trial from the gender wage gap study

A recent study in our lab addressed this question. Children 4 to 9 years old participated in a short task in which they were told stories about a boy and a girl character that did a job for their teacher. They were then told that the teacher wanted to reward the characters but had an unequal number of rewards. This meant that one character would receive more than the other. Children were asked to show the experimenter which character they thought received the more desirable reward.

We found that young girls and boys expected the character with their own gender to be rewarded preferentially. However, a different pattern emerged in older children: Older girls expected the boy and girl to receive the better reward roughly half the time, whereas older boys continued to expect the male character to receive the better reward.

We dove deeper into this pattern by asking whether our findings could be explained by differences in boys’ and girls’ preferences for the characters. That is, maybe boys show a stronger preference for their own gender than do girls. However, this is not what we found. Instead, we found that both boys and girls showed a strong own-gender preference in our follow-up task.

Results from this study suggest that boys and girls have different expectations about how males and females should be rewarded. Boys expect males to be rewarded more, while girls expect equality. While this finding does not map directly onto the gender gap in wages observed in adults, it does suggest an interesting and early-emerging gender difference in how children expect others to be compensated for work.

How do children understand social groups?

In a recent study at our lab, we examined whether children at 5 years and 9 years of age would use the dimensions of warmth and competence to rate a number of social groups the same way that adults would.

Research has shown that all of the characteristics we use to describe people and groups can be boiled down to two fundamental dimensions: warmth (e.g., fairness, kindness, compassion) and competence (e.g., intelligence, ability, assertiveness). These dimensions are important for understanding intergroup attitudes, as the types of attitudes and emotions elicited by a group are often determined by how warm and competent that group is perceived. The Stereotype Content Model (SCM) states that groups seen as both warm and competent are generally admired; these groups are often the majority ingroup in a society. Groups seen as cold and competent are generally envied (e.g., Asian Americans). Groups seen as warm but incompetent are generally pitied (e.g., the elderly), while groups seen as cold and incompetent are generally hated (e.g., drug addicts).

In a recent study at our lab, we examined whether children at 5 years and 9 years of age would use the dimensions of warmth and competence to rate a number of social groups the same way that adults would. We wanted to know if children would use these dimensions independently (that is, understand that kindness does not imply intelligence) and if children would use these dimensions to place commonly known social groups in the warmth by competence space as predicted by the SCM.

Example images depicting different kinds of people

To do this, we created images to depict groups that adults rated as falling into each of the four categories delineated by the SCM. The groups were: Americans and teachers (admired category), scientists and rich people (envied category), blind people and old people (pitied category), and poor people and homeless people (hated category). Then we had children rate the groups’ warmth and competence by asking how nice and how smart they thought the groups were.

We found that in contrast to adults, children do not use these two dimensions independently. Nice and smart ratings for each group were highly correlated, indicating that children consider kindness and intelligence to be similar. When we compared children’s ratings to adults’ ratings, we found that children’s judgments of which groups were smart or not strongly mapped onto adults’ judgments. This indicates that children and adults have similar understandings of what it means to be smart and similar beliefs about which social groups are intelligent. When we examined the warmth ratings, we found that the 5-year-old children’s warmth ratings were not aligned with adults’ ratings but that 9-year-old children’s ratings were. This indicates that children’s understanding of warmth and what it means for a social group to be nice develops slower than their understanding of competence.

Our results suggest that young children have trouble understanding that a social group can be highly competent (and thus high in social status) but not especially warm; they assume that intelligent, powerful groups must be kind as well. These findings hold implications for how children’s intergroup attitudes and beliefs develop and how and when children’s beliefs might differ from adults’ beliefs.

How do children reason about the diverse preferences of others?

We recently conducted studies exploring how young children (3- through 6-year-olds) reason about others on the basis of information about shared likes versus shared dislikes.

We recently conducted studies exploring how young children (3- through 6-year-olds) reason about others on the basis of information about shared likes versus shared dislikes. Specifically, do children make different inferences about individuals who share their feelings regarding a liked food compared with individuals who share their feelings regarding a disliked food?

Two puppets expressing their preferences for various foods

At the start of each session, we asked participants to rate different foods. Next, we introduced participants to puppets that expressed opposing opinions about those foods. Finally, we asked participants questions such as which puppet’s favorite food they would rather eat and which puppet’s favorite toy they would rather play with.

We found that participants viewed individuals who shared their likes and individuals who shared their dislikes as better judges of which foods are tastiest to eat than individuals with opposite preferences. However, shared likes seemed to support broader similarity-based judgments than shared dislikes. For instance, participants viewed individuals who shared their liking for a given food as better judges of toys than individuals who disliked that food, but participants did not view individuals who shared their dislike for a given food as better judges of toys than individuals who liked that food. Our findings suggest that children make rich inferences about others on the basis of shared likes and restricted inferences on the basis of shared dislikes.